Birthing practices and ideologies have gone through many changes throughout history. In AD 98, a Roman named Soranus wrote an obstetrics textbook that was widely used until the 16th century.

Birthing practices and ideologies have gone through many changes throughout history. In AD 98, a Roman named Soranus wrote an obstetrics textbook that was widely used until the 16th century.

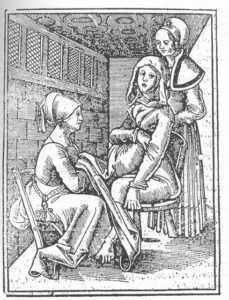

During the Middle Ages, the business of childbirth was in the hands of the midwife, which, in Old English, means “with woman.” Pregnant women were attended by their female friends, relatives and local women who were experienced in helping with childbirth.

Depictions of labor during this time usually show women giving birth in an upright sitting position, using a birthing stool that left space in the seat.

Other positions during this time typically included half-lying positions or even a crouching position, and of course, there were no anesthetics available. However, midwives typically used oils and unguents to help reduce perineal tearing.

There was a significant shift in the business of childbirth during the 1700s. Newer technologies played a role, as did male midwives or physicians, who began taking over for the female midwife. In fact, during this time, female midwives lost much of their status and were portrayed as unhygienic and unenlightened, and they were even associated with witchcraft.

This is the era that heralded the use of certain instruments, such as the forceps and other more destructive tools like the vectis – a lever-type tool for altering the baby’s position – and a crochet tool with a hook, used for extracting a dead fetus from the mother’s body.

The 20th century brought childbirth from the home to the hospital, where hi-tech devices and procedures – such as the fetal heart rate monitor, cesarean sections (C-sections) and epidurals – became commonplace. By the late 1970s in the US, home birth rates fell to around 1%.

The rise of the C-section

Fast forward to the present day, and the business of childbirth looks very different from its early origins. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that there were over 3.9 million births registered in the US in 2012. Of these, over 2.6 million were delivered vaginally, and nearly 1.3 million were delivered via C-section.

Additionally, the vast majority of these births took place in a hospital; only 1.4% of deliveries occurred elsewhere. Of these, over 65% took place at home and 29% occurred in a birthing center.

In 2009, the total C-section delivery rate reached an all-time high, at 32.9%, which represented a 60% increase from the most recent low in 1996, at 20.7% of all births.

Given this significant spike, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) issued clinical guidelines in February of this year to reduce the occurrence of C-sections that were not medically indicated, as well as labor induction before 39 weeks. These guidelines included initiatives aimed at improving prenatal care, changing hospital policies and educating the public.

C-sections are deemed medically necessary when circumstances make a vaginal birth risky for the mother or baby. For example, physicians or midwives may recommend one when the fetus is in the breech position – when the baby’s buttocks or feet are facing the pelvis rather than the head – or when the placenta is covering the cervix – called placenta previa.

We recently reported on a study published in August of this year that suggested breech babies have a higher risk of death from vaginal delivery than C-section.

C-section risks

However, some women opt for elective C-sections when there is no medical reason to do so. Speaking with Medical News Today, Dr. Sinéad O’Neill, of the Irish Centre for Fetal and Neonatal Translational Research, cautioned that this procedure is a serious abdominal surgery that carries certain risks:

“For the mother, these may include infection, clots, hemorrhage, a longer recovery period, and although rare, an increased risk of uterine rupture in subsequent deliveries. For cesarean section babies, respiratory problems requiring treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit are more common.”

She added that women who undergo a C-section may also experience chronic pelvic pain, and some of their babies are at increased risk of developing asthma, diabetes and being overweight.

In July, Dr. O’Neill and her colleagues published a study in PLOS Medicine that suggested a small but significant increased risk of a subsequent stillbirth or ectopic pregnancy following a C-section in a woman’s first birth.

Surgeons performing surgery

“It must be stressed that a cesarean section is an abdominal surgery, and all surgeries carry risks,” said Dr. Sinéad O’Neill.

In detail, the team found that women who had a C-section in their first live birth had a 14% increased rate of stillbirth and a 9% increased risk of ectopic pregnancy in their next pregnancy, compared with women who had a vaginal delivery.

The researchers concluded their study by noting that their findings “will better inform women of the benefits and risks associated with all modes of delivery and help women and their partners make a more informed decision regarding mode of delivery based on their individual pregnancy circumstances.”

Following on from their study published in July, Dr. O’Neill and colleagues conducted research on effects of C-section and fertility – published in the journal Human Reproduction – which suggested that women with a primary C-section were up to 39% less likely to have a subsequent live birth than women who delivered vaginally.

However, Dr. O’Neill added that “this is most likely due to maternal choice to delay or avoid subsequent deliveries as evidenced in the decreasing hazard ratios according to type of cesarean section.”

In an ACOG report on safe prevention of primary C-section delivery, researchers note that “for most pregnancies, which are low-risk, C-section delivery appears to pose greater risk of maternal morbidity and mortality than vaginal delivery.”

Although the National Institutes of Health note that vaginal births after cesarean (VBAC) are successful 60-80% of the time, Dr. O’Neill says that failed VBACs are associated with an increased risk of uterine rupture, and C-sections become riskier with each subsequent surgery.

“Ultimately, midwives and obstetricians must be able to discuss with women their options for birth after a cesarean section and whether a normal birth would be possible drawing from the evidence base and knowledge, and taking into account a woman’s medical history,” she told us.

To drug or not to drug?

Another aspect of childbirth that pregnant women face is how to manage pain. The Bible’s Book of Genesis has God condemning Eve to painful childbirth for eating the forbidden fruit (“In pain you shall bring forth children”), but modern medicine has uncovered causal biological mechanisms behind the pressure women experience during labor.

Pregnancy/labor

During the active labor stage, contractions begin to get stronger, longer and closer together.

There are three stages of labor:

Stage 1: early, active labor

Stage 2: the birth of the baby

Stage 3: delivery of the placenta.

The first stage entails a thinning and opening phase when the cervix dilates and thins out to encourage the baby to move down into the birth canal. This is when women will experience mild contractions in regular intervals that will be less than 5 minutes apart toward the end of early labor.

According to the Mayo Clinic, for first-time moms, the average length of this early labor is between 6-12 hours, and it typically shortens with subsequent deliveries.

Most women report that early labor is not especially uncomfortable, and some even continue with their daily activities.

During the active labor portion of the first stage, however, the contractions begin to get stronger, longer and closer together. Cramping and nausea are common complaints, as is increasing back pressure. This is the time when most women head to the place in which they want to give birth – whether it is at a hospital, birthing center or in a designated area at home.

Active labor can last up to 8 hours, and this is typically when most women who desire an epidural request one.

Spinal and epidural anesthesia are medicines that numb parts of the body in order to block pain. Administered through a catheter placed in the back or shots in or around the spine, these medicines allow the woman to stay awake during labor.

Though these medicines are considered generally safe, they do carry certain risks and complications, such as allergic reactions, bleeding around the spinal column, drop in blood pressure, spinal infections, nerve damage, seizures and severe headache.

Epidural risks

In May of this year, MNT reported on a study conducted by Dr. Robert D’Angelo, of Wake Forest University School of Medicine in North Carolina, and colleagues, which examined the serious complications of anesthesia.

These complications included:

High neuraxial block – an unexpected high level of anesthesia that develops in the central nervous system

Respiratory arrest in labor and delivery

Unrecognized spinal catheter – an undetected infusion of local anesthetic through an accidental puncture of an outer spinal cord membrane.

After examining data on more than 257,000 deliveries between 2004-09, the researchers found that there were only 157 complications reported, 85 of which were anesthesia-related.

They concluded that, given the large sample size, anesthesia complications during childbirth are “very rare.” Though an aim of their study was to identify risk factors associated with the complications in order to devise formal practice guidelines, because the complications linked to anesthesia were so rare, there were too few complications in each category to identify the risk factors.

Dr. D’Angelo told MNT that, following on from their research, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) and the Anesthesia Quality Institute (AQI) have agreed to work together in developing a national serious complication registry for obstetric anesthesia.

He added that the SOAP Serious Complication Taskforce have developed a draft listing serious complications linked to anesthesia, and that AQI have incorporated this information into their website, which is undergoing final testing.

When asked the question of how, in light of other epidural side effects – such as it interfering with the natural birth process or slowing dilation – he would advise women contemplating epidural or natural birth, Dr. D’Angelo told us:

“Unfortunately, childbirth is very painful and no modality relieves labor pain as effectively as epidural analgesia. We do our best to educate patients about the risks and benefits of epidural analgesia, support and encourage natural childbirth when they are considering this option and make ourselves available should they change their minds as labor progresses.”

He added that research suggests epidurals only slow the first stage of labor by 45 minutes and the second stage of labor “by about 15 minutes.”

What can natural and alternative birthing methods offer?

In the wake of increased C-section rates and women opting for medicine-induced pain relief, there are still women who want to do things the natural way – or as close to it as possible.

For such women, there are a number of different options that can help to ease the pain of labor naturally and even prevent certain negative outcomes.

In a study on yoga during pregnancy published in the journal Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, the researchers note that the stress of labor itself can cause changes in a birthing mother’s body:

“Childbirth pain evokes a generalized stress response, which has widespread physiological effects on a woman’s parturient and fetus. Maternal catecholamine production increases, which affects the labor process by reducing the strength, duration and coordination of uterine contractions.”

By managing this stress response, laboring women “have been able to transcend pain and experience psychological and spiritual comfort,” the researchers add.

In their study, they found that an experimental group of women who were randomized to participate in a yoga program during gestation had higher levels of maternal comfort during labor, experienced less labor pain, and had a shorter duration of the first stage of labor as well as the total time of labor, compared with a control group that did not participate in the yoga program.

Hypnosis for pain relief

Another study that investigated the effect of hypnosis on labor and birth outcomes in pregnant adolescents found that the hypnosis group showed better outcomes in terms of complicated deliveries, surgical procedures and length of hospital stay, compared with a control group.

Pregnancy yoga

Techniques such as pregnancy yoga during gestation and hypnosis training can reduce anxiety and improve pain tolerance during labor.

The researchers from that study – published in the Journal of Family Practice and led by Dr. Paul G. Schauble – note that hypnosis has been used for pain control during labor and delivery for more than a century, but that the introduction of anesthetics during the late 19th century led to its decline.

“The use of hypnosis in preparing the patient for labor and delivery is based on the premise that such preparation reduces anxiety, improves pain tolerance (lowering the need for medication), reduces birth complications, and promotes a rapid recovery process,” they add.

Through this method, participants gain a sense of active participation and control by learning about the birthing process and alternative ways to produce anesthesia within the body naturally, through the release of endorphins – pain-fighting neurotransmitters.

Because water has endorphin-releasing effects on the body, many women also opt to combine their hypnosis method with a water birth, which employs the use of a birthing pool.

“Research done thus far indicates that the use of hypnosis consistently reduces anesthesia complications and facilitates a reduction in discomfort and medication during the labor and delivery process,” Dr. Schauble told MNT.

He added:

“I would strongly encourage women who were currently developing their birth plans to consider the addition of hypnosis as a means of preparing for the labor delivery process, thus increasing the likelihood of a comfortable and healthy birthing process.”

In the UK and the US, a method called HypnoBirthing is taught by practitioners in various areas.

Though there are a number of different options women can consider for their birth plans, experts from all approaches are in agreement that women should educate themselves and speak with their midwives or physicians in order to determine the course that is best for them.

MNT DT